“The past,” Phillip Lopate says, “is an Aladdin’s lamp we never tire of rubbing.”

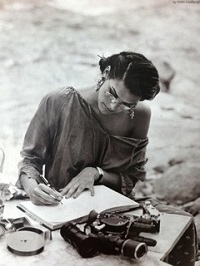

Guest Blogger Norma Watkins studied with Phillip Lopate. The following is what she gleaned working with the master of the personal essay.

The hallmark of personal essay and memoir is its intimacy. [Links below on memoir writing.]

In a personal essay, the writer seems to be speaking directly into the reader’s ear, confiding everything from gossip to wisdom: thoughts, memories, desires, complaints, whimsies.

The core of this kind of writing is the understanding that there is a certain unity to human experience. As Montaigne put it, “Every man has within himself the entire human condition.”

This kind of informal writing, whether a short piece or a book of memoir, is characterized by:

- self-revelation

- individual tastes and experiences

- a confidential manner

- humor

- a graceful style

- rambling structure

- unconventionality

- novelty of theme

- freshness of form

- freedom from stiffness and affectation

The informal writing of the personal essay and memoir offers an opportunity toward candor and self-disclosure. Compared with the formal essay, it depends less on airtight reasoning and more on style and personality. We want to hear the writer’s voice.

How do we achieve this?

Use a conversational tone. Instead of seeing our memoirs as collections of facts we are leaving to the future, strive to write as if this were a letter to a friend.

We have a contract to the reader to be as honest as possible.

Humans are incorrigibly self-deceiving, rationalizing animals. Few of us are honest for long. Often, in shorter personal essays, the “plot,” its drama and suspense, consists in watching how far the essayist can drop past her psychic defenses toward deeper levels of honesty. You want to awaken in the reader that shiver of self-recognition.

Remove the mask. Vulnerability is essential.

The reader will forgive the memoirist’s self-absorption in return for the warmth of his candor.

The writer must be a reliable narrator. We must trust that the homework of introspection has been done. Part of this trust comes, paradoxically, from the writer’s exposure of her own betrayals, uncertainties, and self-mistrust. This does not mean relentlessly exposing dark secrets about ourselves, so much as having the courage to cringe in retrospect at our insensitivity that wounded another, a lack of empathy, or the callowness of youth. As readers, we want to see how the world comes at another person, the irritations, jubilations, aches and pains, humorous flashes. These are your building blocks.

Ask yourself questions and follow the clues. Interrogate your ignorance. Be intrigued by limitations, physical and mental, what you don’t understand or didn’t do.

Develop a taste for littleness, including self-belittlement. Learn to look closely at the small, humble matters of life. Develop the ability to turn anything close at hand into a grand meditational adventure. Make a small room loom large by finding the borders, limits, defects and disabilities of the particular. Start with the human package you own. Point out these limitations, which will give you a degree of detachment.

You confess and, like Houdini, you escape the reader’s censure by claiming: I am more than the perpetrator of that shameful act; I am the knower and commentator as well. If tragedy ennobles people and comedy cuts them down, personal writing with its ironic deflations and its insistence on human frailty tilts toward the comic. We end by showing a humanity enlarged by complexity.

We drop one mask only to put on another but if in memoir we continue to unmask ourselves, the result may be a genuine unmasking. In the meantime, the writer tries to make his many partial selves dance to the same beat: to unite through force of voice and style these discordant, fragmentary parts of ourselves. A harvesting of self-contradiction is an intrinsic part of the memoir. Our goal is not to win the audience’s unqualified love but to present the complex portrait of a human being.

A memoirist is entitled to move in a linear direction, accruing extra points of psychological or social shading as time and events pass. The enemy is always self-righteousness, not just because it is tiresome, but because it slows down the self-questioning. The writer is always examining his prejudices, his potential culpability, if only through mental temptation.

Some people find a memoir egotistical, all that I, I, I, but there are distinctions between pleasurable and irritating egotism. Writing about oneself is not offensive if it is modest, truthful, without boastfulness, self-sufficiency, or vanity. If a man is worth knowing, he is worth knowing well. It’s a tricky balance: a person can write about herself from angles that are charmed, fond, delightfully nervy; alter the lens a little and she crosses into gloating, pettiness, defensiveness, score-settling (which includes self-hate), or whining about victimization. The trick is to realize we are not important except as an example that can serve to make readers feel a little less lonely and freakish.

The Past, as we said in the beginning, is a lamp we never tire of rubbing. We are writing the tiny snail track we made ourselves. Such writing is the fruit of ripened experience. It is difficult to write from the middle of confusion. We need enough distance to look back at the choices made, the roads not taken, the limiting family and historic circumstances, and what might be called the catastrophe of personality.

Finally, the memoirist must be a good storyteller. We hear, “Show, don’t tell,” but the memoirist is free to tell as much as she likes, while dropping into storytelling devices whenever she likes: descriptions of character and place, incident, dialogue and conflict. A good memoirist is like a cook who learns, through trial and error, just when to add another spice to the stew.

The Art of the Personal Essay, Phillip Lopate, Doubleday, 1994.

Note from Marlene: For more suggestions about how to write a personal essay, please see Write Spot Blog posts:

How to Write A Memoir-Part One

How to Write A Memoir-Part Two

Norma Watkins will be the Writers Forum Presenter on August 18, 2016: “Writing Memoir and How To Turn Your Stories Into Fiction.”

Norma grew up in Mississippi and left in the midst of the 1960s civil rights struggles. Her award-winning memoir, The Last Resort: Taking the Mississippi Cure, tells the story of those years. When asked what the memoir is about, Watkins says: “Civil rights, women wronged, good food and bad sex.”

Watkins has a Ph.D. in English and an MFA in Creative Writing. She teaches Creative Writing for Mendocino College and serves on the Board of the Mendocino Coast Writers Conference, and the Coast branch of the California’s Writers Club.