Why I Love Writing Ekphrastic Poetry by Guest Blogger, Robin Gabbert

Yes, I do love writing ekphrastic poetry! It’s poetry that never requires a prompt besides the piece of art you are viewing — be it a painting, a sculpture, a collage, digital rendering, or other artistic presentation such as dance, drama, and music (so hearing counts). You don’t have to search for writing prompts beyond your nearest museum or gallery (or their website) or a visit to WikiArt or Google Arts & Culture to search for your favorite artist or browse for something new that sparks your imagination.

Ekphrastic poetry has been with us since at least the time of Homer and has been used by many of our best poets. An early example is John Keats “Ode on a Grecian Urn.”

Rainer Maria Rilke was another advocate as shown in his beautifully descriptive poem “Archaic Torso of Apollo.”

Modern poets like W.H. Auden, William Carlos Williams, Anne Sexton, and Anne Carson have also written ekphrastic poetry to art as diverse as Bruegel’s “The Fall of Icarus” to “Van Gogh’s Starry Night” and Edward Hopper’s “Nighthawks.”

My contribution to this genre is “The Clandestine Life of Paintings in Poems.”

Do you know that paintings can tell stories? Perhaps you do. But do you also know that they can tell secrets as well – whispering unexpected confidences and tales to their friends, especially poets?

That is how I approach ekphrastic poetry. What does this painting want to tell me? In what way can I best “enter” the art? It might be, what did the artist want to tell me?— but not necessarily.

It might instead be, “What is that dog curled at his master’s feet thinking?” or “What is really on the mind of that nude woman stretched across the divan?”

What feeling does the painting evoke in the viewer, in me? Does it relate to some issue I care about? Is there an ambiguity in the art that can be explored?

Abstracts and surreal paintings can be fun to write about because, rather than a story, they tend to bring up feelings, emotions and then challenge you to evoke in your poem both the painting, and what you discern from it, in a way that is relatable to the reader.

Here are a few examples of ekphrastic poems, starting with the very simple, including explanations of how I approached them, how I “entered” the art.

I Know How You Feel

Little brown leaf caught

by the sun, in mid-flutter.

I too, sometimes

just want to curl-in on myself

and hope for a soft landing.

This simple sweet image evoked a feeling in me, which I translated into a short, simple poem. The poem gave feelings to a small leaf so that I could express my own feelings, by empathizing with it.

This next poem, “Yelo Moon,“ is different. The title character in this striking watercolor is so large and so vivid, it demands attention. It demanded that I make him (funny how it had to be a “him”) the Center of Attention. So, I did.

Yelo Moon

After a watercolor of the same name

by Marion Stern

The glowing saffron globe

pulls itself into the night sky

and seems to float

in the wetland marsh,

reflecting, observing

its gleaming face in the salty water.

As if to say—

See,

I am not made of green cheese!

Behold me with wonder—

I light the sky, I light the land.

Marsh grasses, cower before me!

I pull the tides like stretching rubber bands,

leaving crabs to flounder and unwary boats askew.

But the sea grasses and marsh creatures know

that, as the braggart rises, his reflection will

shrink along with

his delusions of grandeur.

After the bragging moon had his say, of course, he had to be brought back down to earth. Thus, the last stanza is written from the point of view of the surrounding plants and animals that are listening to the moon go on and on about how great he is, letting us know that they are not buying into his PR spiel.

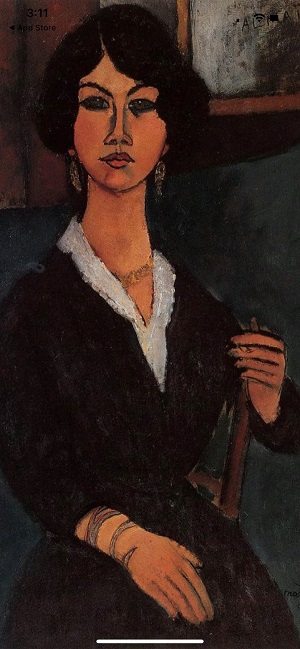

Another technique I use in writing ekphrastic poetry is to invent a fictional story based on a person in a painting. In “Clandestine Life of Paintings in Poems, it was a portrait of a woman by Amedeo Modigliani— an artist who does amazing portraits, portraits you could stare at all day because the people in them are so fascinating, mesmerizing. The name of the painting was simply “Amaisa.” In my poem, she became “The Woman with the Wrist Tattoo.”

The Woman with the Wrist Tattoo

Based on Amaisa by Amedeo Modigliani

The woman across the room

seems upset, trying not to look

at anyone, she focuses on the door.

Eyes, two shining coals

rimmed with sorrow

She lights a cigarette,

but lets the fire burn down

until the ash is almost at her hand.

Her lipstick slightly smeared

on pillowed lips.

Swallowing, she pulls herself upright,

assumes an iron face

and greets the man who’s just entered—

Hello Claude,

She puts out the cigarette.

Don’t look so surprised,

(this is Claude’s favorite club

not a place she is expected).

do you think I don’t know

that you’re not here

when you tell me you’re

going for a cigar and brandy

with Maurice?

Do you think I don’t smell

the stink of attar and ashes

from your dalliance with the

vicinal char girl?

Well, I’ve had enough.

I used your long absence

to get this reminder of you—

she says extending her arm—

the snake who slithered up my sleeve

and into my heart, the serpent who

stole my fortune and dignity

When people ask about

the tattoo at my wrist,

I’ll just tell them—

Oh, that’s Claude, a snake

I once knew

But really, it’s just a reminder that,

if you again try to take my hand,

I should pull it back…

To avoid the sting.

These are just a few of the ways one can “enter” a piece of art to write a poem. Other ways include exploring the spiritual aspects the painting may suggest, or the purely emotional aspects. Of course, paintings and other art can suggest all manner of issues to write about including social issues, relationship issues, and all the diverse items that your brain can connect to an image! Don’t go in with a preconceived notion, just look at the art and give your mind free reign. You may be surprised what the painting has to tell you.

Robin Gabbert has poems in Redwood Writer Poetry anthologies, California Writers Club Literary Reviews and in “The Best Haiku” 2022 international anthology from Haiku Crush.

Robin’s books, “Diary of a Mad Poet” and “The Clandestine Life of Paintings, in Poems”are available on Amazon.

Several of her haiku, tankas, and haibuns appear in the anthology, “Burro in My Kitchen,”published byBlue Light Press.

Robin lives in California wine country with her Dutch husband, Con Jager, and pup Hamish.

available on Amazon.